Launching the ‘State of DPI’ Project

Mapping the global state of digital public infrastructure

By Anjum Dhamija, David Eaves, Krisstina Rao & Jordan Sandman

We are excited to announce the launch of a digital public infrastructure (DPI) baseline research project – the ‘Global State of DPI’. Over the past year, the conversation around DPI has dramatically expanded. Most notably, the G20’s endorsement of DPI as a critical catalyst for countries' development has brought global attention to the concept of “infrastructure thinking” for development and public service delivery.

The launch of the 50-in-5 campaign demonstrated a commitment by a global coalition of partners including Co-Develop to align around a shared goal in supporting the adoption of safe and inclusive digital public infrastructure globally.

As momentum, attention, and investment surrounding DPI for development increase, there are several urgent areas that would benefit from ecosystem-wide convergence. The first is a better understanding of the current global adoption of DPI at the country level among civil society groups, implementers, and researchers. The second is to understand where gaps and opportunities exist for development actors to support DPI adoption and safeguarding.

In order to meet these objectives this project will focus on two research objectives:

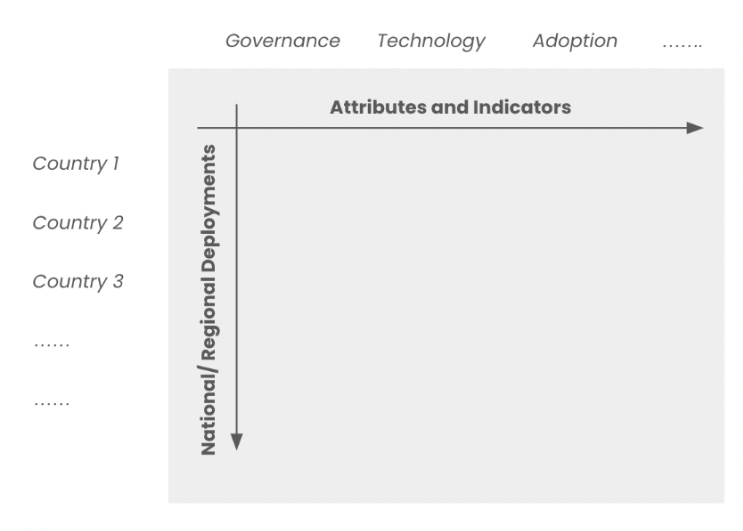

What makes a DPI? Bring together a set of attributes and indicators that characterise DPI deployments

Where are the DPIs? Understanding which countries have deployed technology that has the attributes of DPI

Our research treats ID programs, payment systems and data exchanges as core DPI components– aligning with the World Bank, the Gates Foundation, and our earlier work. For us, these core DPI components are society-wide, digital capabilities that are essential to participation in society and markets. Gathering data to study at least 200 deployments (including IDs, payment systems, and data exchanges), we scrutinised how they were designed and how they have fared since they were deployed.

Through this research, we are excited to unpack insights that we hope will move us closer to understanding the ‘Global State of DPI.’ First, a list of DPI attributes and indicators helps us understand what makes a DPI. Second, a DPI repository analyzes what countries have deployed ID, payments and data exchange and assesses the extent to which deployments align with the DPI attributes and indicators.

What makes a DPI?

Here, we started assessing the characteristics of the deployments we studied against a conceptual understanding of DPI systems. The characteristics were framed as a list of attributes of ID programs, payment systems, and data exchanges. ‘DPI Indicators’ were derived through two iterations. First, through a top-down document analysis of relevant definitional resources, as published by CDPI, UNDP World Bank, BMGF, and Co-Develop, we identified conceptual attributes that define each of the three DPI components. Second, a ‘bottom-up’ process of identifying characteristics of DPI, across their design and outcomes as they are instantiated in countries. By leveraging insights from the DPI repository, as well as from a literature review of key contributors to each of these DPI components (ID4D, CGAP, Africa Nenda, X-Road), we were able to deduce a list of indicators that represent manifestations of these attributes.

We found that:

Principles that guide the development of physical infrastructure also inform the development and deployment of digital public infrastructure. These principles, namely inclusion, accountability, and interoperability, are common to all core DPI but manifest differently across core DPI systems. For example, accountability in ID programs typically relies on an ID authority – independent of political influence – that can legally and securely collect and store individual data. In contrast, payment systems often create accountable structures in the absence of a public owner. Payment switches, frequently set up by private bank associations, may have a regulated requirement to be governed by a public interest scheme to ensure transactions are conducted in a responsible way.

Attributes of DPI can be grouped into three categories: governance, technology, and adoption indicators. For payment systems, setting up real-time payment infrastructure is a technological consideration. However, the rules around using a switch, and at what cost, are governance considerations that will need the intervention of the scheme governor. While offering a direction on their scope of implementation (i.e. governance indicators need to be grounded in through policy and legislative processes), this grouping also tests if there are multiple ways to fulfil a specific attribute.

Where are the DPIs?

We began to explore ID programs, payment systems, and data exchanges in geographies where DPI deployments have the most potential to contribute to the fulfilment of the Sustainable Development Goals. Identifying the characteristics of DPI components that are well known, we first standardised the data available across global deployments for these characteristics (i.e. name, scale of adoption, ownership and distribution features, etc.). Here, we relied on secondary sources of information (government press releases, credible third-party reports and DPG/DPI publications) as well as primary interviews with government officials, third-party implementers and funders.

Some initial highlights of what we have found include:

While many countries have an ID program, they operate at different scales and with varying levels of enrolment, use and digital interoperability. Dependencies on private technology vendors can exist at the technology design stage (using data collection systems from a specific vendor) or even for functional uses (relying on private e-authentication services).

Some regions offer specific insights into the design of national payment systems as DPI. Specifically in Africa, every country has at least one instant payment system planned or in operation. Around 60% are publicly owned and governed. Very few of them are closed-loop. In some countries, regional payment systems might replace the need for a domestic IPS. The need for nationalised DPI systems may have to be reconsidered for certain societal functions.

A large number of data exchanges are either leveraging X-Road’s open-source code base, or using proprietary solutions based on X-Road’s architecture. However, there are also implementations beyond these that enable data sharing, with different nomenclature such as ‘API exchange’ and ‘interoperability platform’, reflecting differences in technological and governance considerations.

What Comes Next

Our project seeks to understand the characteristics of in-development and deployed DPI systems and provide a path to help countries adopt new DPI or mould their existing systems towards safe and inclusive infrastructures. We do not intend to isolate and valorize DPI systems from those that do not meet a set of criteria. Meeting each of the DPI indicators is a challenging task that requires technological and operational capacity, political will, and socio-economic incentives.

This project seeks to inform how digital systems can mature and progress over time into infrastructure. It also acts as a foundation for a systemic analysis of the global state of DPI that we hope others can and will build upon. In the coming months, we look forward to co-developing a better understanding of the ‘Global State of DPI’. Share your contributions through consultations, slated to be organized in the coming quarter, or get in touch with us to contribute to the repository on DPI deployments.